Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Monday, December 7, 2009

Friday, December 4, 2009

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Monday, November 30, 2009

Monday, November 23, 2009

Friday, November 20, 2009

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Friday, November 13, 2009

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Monday, November 9, 2009

Friday, November 6, 2009

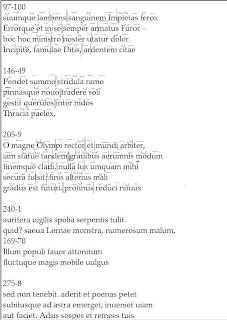

scansion 830 and Sapphic Hendecasyllables

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Monday, November 2, 2009

Friday, October 30, 2009

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Monday, October 26, 2009

Friday, October 23, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

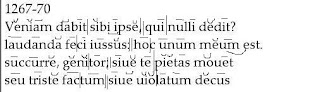

Aeolic Meters and the Lesser Asclepiadean, Scansion 524-7

Greek meter (and Latin meter in imitation of Greek forms) includes one group of meters called Aeolic because many of these types of meters were used by poets who spoke the Aeolic Greek dialect, primarily Sappho and Alcaeus.

Meters that are composed chiefly of choriambs (long short short long), cretics (long short long), and other iambic forms (iamb u-, spondee --, bacchiac u--) are usually called Aeolic meters.

The glyconic and pherecratean are two of the most common aeolic meters.

The glyconic is xx | -uu- | u -. The pherecratean is a catalectic version of a glyconic (xx | -uu- | -). Catalectic means that part (usually one syllable) is missing. Often catalectic versions of meters will be used to end a stanza in stanzaic verse. Thus Catullus uses a stanza of 3 glyconics + 1 pherecratean in poem 34.

Another glyconic meter is Catullus' favorite the hendecasyllabic (or 11-syllable: xx | -uu- | u- | u--) verse as in poem 1. It scans with two ancipites or unknown syllables (in Catullus the first is long); then it has a choriamb, an iamb, and a bacchiac.

We are learning the Aeolic Meter called the Lesser Asclepiadean which Seneca uses in the chorus starting at 524.

It scans -- | -uu- | -uu- | u- which is spondee, choriamb, choriamb, iamb.

There is always (at least here in Seneca) a word break or caesura between the two choriambs in the middle of the line.

Note that this meter always scans the same line after line, so once you mark all the elisions it should be VERY EASY.

Meters that are composed chiefly of choriambs (long short short long), cretics (long short long), and other iambic forms (iamb u-, spondee --, bacchiac u--) are usually called Aeolic meters.

The glyconic and pherecratean are two of the most common aeolic meters.

The glyconic is xx | -uu- | u -. The pherecratean is a catalectic version of a glyconic (xx | -uu- | -). Catalectic means that part (usually one syllable) is missing. Often catalectic versions of meters will be used to end a stanza in stanzaic verse. Thus Catullus uses a stanza of 3 glyconics + 1 pherecratean in poem 34.

Another glyconic meter is Catullus' favorite the hendecasyllabic (or 11-syllable: xx | -uu- | u- | u--) verse as in poem 1. It scans with two ancipites or unknown syllables (in Catullus the first is long); then it has a choriamb, an iamb, and a bacchiac.

We are learning the Aeolic Meter called the Lesser Asclepiadean which Seneca uses in the chorus starting at 524.

It scans -- | -uu- | -uu- | u- which is spondee, choriamb, choriamb, iamb.

There is always (at least here in Seneca) a word break or caesura between the two choriambs in the middle of the line.

Note that this meter always scans the same line after line, so once you mark all the elisions it should be VERY EASY.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Friday, October 9, 2009

Stichomythic script, HF 406-38

This script is the collective work of the following students from this class (Latin 316, Franklin and Marshall, Fall 2009):

Brad Boileau, Theresa Burke, Celine Chao, Paulette Cutruzzula, Kyle English, Stephanie Fuga, Anna Hall, Megan Helsel, Matt Holt, Erica Koppenhoeffer, Ariel Kornhauser, Zachary Leh, and Becca Patterson.

It was compiled and edited by myself, Abram Ring, for us to stage a dramatic reading performed by Ariel Kornhauser and Amanda Fox on Friday, Oct. 9, 2009. Anyone may access this translation for personal or educational use. However, it should not be included in a for-profit publication without contacting myself as the editor, and it should be cited by giving full credit to all the translators as would any translation since it is an original artistic creation and thus subject to copyright.

Script

LY. But that man for his own kingdom, and I* led on by wicked desire? The end of war is sought, not the cause. But now, let all of the memory pass away: when the victor has set down arms, it is fitting also that the conquered put aside hatred*. I* do not entreat you to pay homage to a ruler on bent knee: this of itself is pleasing that with a great spirit you embrace your ruin*. You are a worthy spouse for a king (or "be a spouse worthy of a king"). Let us join marriage beds.

* poetic pl. in Latin

ME. Icy trembling rushes through my bloodless limbs. What crime struck my ears? Truly I hardly shuddered when with peace smashed a warlike crash echoed round the walls, fearlessly I endured it all. I tremble at your bed; now I seem to myself captured. Now let the chains weigh down my body and let slow death be prolonged by long hunger. No power will conquer my* faith; I will die yours, Alcides.

*poetic pl.

LY. Does your spouse buried below produce such feelings?

ME. He touched the underworld in order that he could pursue higher places.

LY. That burden of immense earth overwhelms him.

ME. He will be crushed by no burden, he who bore the heavens.

LY. You will be forced.

ME. He who can be forced does not know how to die.

LY. Say what better regal service I may prepare for the new marriage.

ME. Either your death or mine.

LY. You will die, demented one.

ME. I will meet my husband.

LY. Surely to you a slave* is not better than our scepter?

*household slave, born at home, not bought

ME. How many kings that "slave" has given to death!

LY. Why therefore does he serve a king and suffer the yoke?

ME. Remove the harsh commands, what will virtue be?

LY. Do you suppose it virtue to be thrown before beasts and monsters?

ME. It is the nature of virtue to subdue those things which all men fear.

LY. The Tartarean shades oppress him boasting*.

*Literally "speaking big (words)"

ME. There is no easy way from the earth* to the stars.

*poetic pl.

LY. Born of what father does he hope for the palaces of heaven*?

*Actually of the "heavenly ones", i.e. "the gods"

Brad Boileau, Theresa Burke, Celine Chao, Paulette Cutruzzula, Kyle English, Stephanie Fuga, Anna Hall, Megan Helsel, Matt Holt, Erica Koppenhoeffer, Ariel Kornhauser, Zachary Leh, and Becca Patterson.

It was compiled and edited by myself, Abram Ring, for us to stage a dramatic reading performed by Ariel Kornhauser and Amanda Fox on Friday, Oct. 9, 2009. Anyone may access this translation for personal or educational use. However, it should not be included in a for-profit publication without contacting myself as the editor, and it should be cited by giving full credit to all the translators as would any translation since it is an original artistic creation and thus subject to copyright.

Script

LY. But that man for his own kingdom, and I* led on by wicked desire? The end of war is sought, not the cause. But now, let all of the memory pass away: when the victor has set down arms, it is fitting also that the conquered put aside hatred*. I* do not entreat you to pay homage to a ruler on bent knee: this of itself is pleasing that with a great spirit you embrace your ruin*. You are a worthy spouse for a king (or "be a spouse worthy of a king"). Let us join marriage beds.

* poetic pl. in Latin

ME. Icy trembling rushes through my bloodless limbs. What crime struck my ears? Truly I hardly shuddered when with peace smashed a warlike crash echoed round the walls, fearlessly I endured it all. I tremble at your bed; now I seem to myself captured. Now let the chains weigh down my body and let slow death be prolonged by long hunger. No power will conquer my* faith; I will die yours, Alcides.

*poetic pl.

LY. Does your spouse buried below produce such feelings?

ME. He touched the underworld in order that he could pursue higher places.

LY. That burden of immense earth overwhelms him.

ME. He will be crushed by no burden, he who bore the heavens.

LY. You will be forced.

ME. He who can be forced does not know how to die.

LY. Say what better regal service I may prepare for the new marriage.

ME. Either your death or mine.

LY. You will die, demented one.

ME. I will meet my husband.

LY. Surely to you a slave* is not better than our scepter?

*household slave, born at home, not bought

ME. How many kings that "slave" has given to death!

LY. Why therefore does he serve a king and suffer the yoke?

ME. Remove the harsh commands, what will virtue be?

LY. Do you suppose it virtue to be thrown before beasts and monsters?

ME. It is the nature of virtue to subdue those things which all men fear.

LY. The Tartarean shades oppress him boasting*.

*Literally "speaking big (words)"

ME. There is no easy way from the earth* to the stars.

*poetic pl.

LY. Born of what father does he hope for the palaces of heaven*?

*Actually of the "heavenly ones", i.e. "the gods"

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Friday, October 2, 2009

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Hercules' myths

Here are the canonical 12 labors

1. Slay the Nemean Lion.

2. Slay the 9-headed Lernaean Hydra (and the crab who helped the hydra).

3. Capture the Golden Hind of Artemis.

4. Capture the Erymanthian Boar.

5. Clean the Augean stables in a single day.

6. Slay (or scare away) the Stymphalian Birds.

7. Capture the Cretan Bull.

8. Get the Man-eating Mares of Diomedes.

9. Obtain the Girdle of the Amazon Queen.

10. Obtain the Cattle of Three-headed Geryon.

11. Get the Apples of the Hesperides.

12. Capture Cerberus.

There are many other stories about Hercules (Herakles in transliterated Greek). One of the best websites on myth is http://www.theoi.com/greek-mythology/heracles.html which has many ancient Roman and Greek texts in translation. For example, they have Diodorus Siculus' history of Heracles (yes, the Greeks thought he was real although they did not agree about who exactly he was--or they were, since there were more than one Heracles--or what he did):

http://www.theoi.com/Text/DiodorusSiculus4A.html#8

1. Slay the Nemean Lion.

2. Slay the 9-headed Lernaean Hydra (and the crab who helped the hydra).

3. Capture the Golden Hind of Artemis.

4. Capture the Erymanthian Boar.

5. Clean the Augean stables in a single day.

6. Slay (or scare away) the Stymphalian Birds.

7. Capture the Cretan Bull.

8. Get the Man-eating Mares of Diomedes.

9. Obtain the Girdle of the Amazon Queen.

10. Obtain the Cattle of Three-headed Geryon.

11. Get the Apples of the Hesperides.

12. Capture Cerberus.

There are many other stories about Hercules (Herakles in transliterated Greek). One of the best websites on myth is http://www.theoi.com/greek-mythology/heracles.html which has many ancient Roman and Greek texts in translation. For example, they have Diodorus Siculus' history of Heracles (yes, the Greeks thought he was real although they did not agree about who exactly he was--or they were, since there were more than one Heracles--or what he did):

http://www.theoi.com/Text/DiodorusSiculus4A.html#8

Friday, September 25, 2009

Monday, September 21, 2009

Class Wednesday Sept. 23, Euripides, Herakles

Here is one translation of HF for when I ask you to read a section in

translation:

http://www.theoi.com/Text/SenecaHerculesFurens.html

That is the old Loeb. The new Loeb by Fitch is in the department

library in Goethean.

For next class, we will be doing something different by reading

English, a translation of Euripides. You need not read the same one,

but it may help to do so. I am attaching Vellacott's translation of

Euripides Heracles and I also uploaded it to edisk.

If you get a chance to read Vellacott's intro, it may help you

understand Euripides' artistry (i.e. what he is trying to show).

I know that you will not have read the HF completely yet, but you have

read Fitch's Intro which described the plot. I think it will be good

for all of you to familiarize yourselves with Euripides' version,

which is Seneca's primary model though he may have consulted a later

Greek or Roman version of the story too. Some of you may want to do a

comparative paper for this class--looking at specific differences

between the two.

Things to consider while reading Euripides:

1. How does the Introduction compare with what we have read so far in

Seneca? How does this change our view of Heracles or any other

characters?

2. In Seneca Lycus attempts to marry Megara. This is not in

Euripides. Why do you think Seneca did this?

3. In Seneca (not in Euripides), we have Theseus giving a vivid

description of Hercules exploits in Hades. How does that affect our

view of Hercules?

4. In Euripides (as commonly for such scenes in Greek tragedy), the

murder actually occurs off-stage and is reported by a messenger.

Fitch suggests (possibly correctly) that Seneca has followed a later

model in staging the murder. On the other hand, he may have decided to

do this on his own. How does this choice whether original or derived

from a second model affect the drama and our reception? Does this

affect our view of the performance question?

5. I think you will find a major difference between the character of

Euripides' Heracles and Seneca's Hercules. Try to come up with some

specific points of dissimilarity and consider how this might reveal

what the poets were trying to do. Also do you like one author's

Heracles more than the other? If so, why, and does this mean that you

prefer that author's play?

translation:

http://www.theoi.com/Text/SenecaHerculesFurens.html

That is the old Loeb. The new Loeb by Fitch is in the department

library in Goethean.

For next class, we will be doing something different by reading

English, a translation of Euripides. You need not read the same one,

but it may help to do so. I am attaching Vellacott's translation of

Euripides Heracles and I also uploaded it to edisk.

If you get a chance to read Vellacott's intro, it may help you

understand Euripides' artistry (i.e. what he is trying to show).

I know that you will not have read the HF completely yet, but you have

read Fitch's Intro which described the plot. I think it will be good

for all of you to familiarize yourselves with Euripides' version,

which is Seneca's primary model though he may have consulted a later

Greek or Roman version of the story too. Some of you may want to do a

comparative paper for this class--looking at specific differences

between the two.

Things to consider while reading Euripides:

1. How does the Introduction compare with what we have read so far in

Seneca? How does this change our view of Heracles or any other

characters?

2. In Seneca Lycus attempts to marry Megara. This is not in

Euripides. Why do you think Seneca did this?

3. In Seneca (not in Euripides), we have Theseus giving a vivid

description of Hercules exploits in Hades. How does that affect our

view of Hercules?

4. In Euripides (as commonly for such scenes in Greek tragedy), the

murder actually occurs off-stage and is reported by a messenger.

Fitch suggests (possibly correctly) that Seneca has followed a later

model in staging the murder. On the other hand, he may have decided to

do this on his own. How does this choice whether original or derived

from a second model affect the drama and our reception? Does this

affect our view of the performance question?

5. I think you will find a major difference between the character of

Euripides' Heracles and Seneca's Hercules. Try to come up with some

specific points of dissimilarity and consider how this might reveal

what the poets were trying to do. Also do you like one author's

Heracles more than the other? If so, why, and does this mean that you

prefer that author's play?

Friday, September 18, 2009

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Monday, September 14, 2009

translation 92-104

reuocabo in alta conditam caligine,

ultra nocentum* exilia, discordem deam

quam munit ingens montis oppositi specus;

*nocens as you might expect from the derivative innocent sometimes means not "harming" but "guilty"

I will call back the the one cloaked/concealed in lofty mist,

(from) beyond the exiles of the guilty, (I will call back) the discordant goddess

whom the huge cave of an obstructing mountain walls off.

There is some minor alliteration at the end of lines 92 & 93.

discordem deam is no doubt meant to recall Vergil's Discordia, Aen. 6.280 & 8.702.

As Fitch explains, the cave seems to be a hollow subterranean prison inside a mountain. I am not sure that I agree about changing oppositi to impositi--this doesn't help much in my opinion. The wording is strange but this is poetry after all.

95

educam et imo* Ditis e regno extraham

quidquid relictum est: ueniet inuisum Scelus

suumque lambens sanguinem Impietas ferox

Errorque et in se semper armatus Furor –

hoc hoc^ ministro~ noster utatur dolor.

^notice the anaphora (repetition) reflecting Juno's emotional state

~ablative object of utor

*like medius ("middle of"), imus can have a partitive meaning ("lowest part of" instead of just "lowest") as I suspect is true here.

I shall draw her forth and will drag out of the lowest (part of) the kingdom of Dis whatever is left over. There will come hated Crime, and ferocious Impiety licking her own blood and Error and Madness (who is) always armed against himself. This, this servant let our Grief employ. (I.e. Let our grief employ this as its servant.)

100

Incipite, famulae Ditis, ardentem citae

concutite pinum et agmen horrendum anguibus* *ablative of cause, similar to means

Megaera ducat atque luctifica manu

uastam rogo* flagrante corripiat trabem. *ablative of separation

hoc agite, poenas petite uiolatae Stygis*; *objective genitive

Begin, maidservants of Dis, roused (or as adverb "excitedly/madly") shake the burning pine and let Megaera lead your squad horrible with snakes and let her snatch with her grief-causing hand a vast log from a flaming pyre! Do this, seek out the penalties (i.e. revenge) for the violated/desecrated Styx.

By the way, I prefer vitiatae (E) over violatae (A) in line 104 because lectio difficilior potior est (The more difficult reading is the better one). This is a rule of textual criticism that says that given that there are two possible readings (and there are not other strong grounds for choosing between them), if one of the readings is quite easy to understand while the other is more difficult, the more difficult reading is more likely to be correct since it is less likely that someone would complicate the text than that they would accidentally or even purposefully banalize it (that is, explain away the difficulty by replacing it with a very easy to understand alternative). Personally I like the metaphorical meaning of vitiatae. Violatae is much more common and can mean physically violated in many different ways. Vitiatae implies corruption or befoulment, and one of the common senses of vitiare is "to deflower" or "to rape". Juno's feminine anger against Hercules' super-machoism may be displaying itself here. You should know that, besides being a river, Styx was also a very powerful goddess whom Zeus entrusted to watch over the oaths of the gods.

ultra nocentum* exilia, discordem deam

quam munit ingens montis oppositi specus;

*nocens as you might expect from the derivative innocent sometimes means not "harming" but "guilty"

I will call back the the one cloaked/concealed in lofty mist,

(from) beyond the exiles of the guilty, (I will call back) the discordant goddess

whom the huge cave of an obstructing mountain walls off.

There is some minor alliteration at the end of lines 92 & 93.

discordem deam is no doubt meant to recall Vergil's Discordia, Aen. 6.280 & 8.702.

As Fitch explains, the cave seems to be a hollow subterranean prison inside a mountain. I am not sure that I agree about changing oppositi to impositi--this doesn't help much in my opinion. The wording is strange but this is poetry after all.

95

educam et imo* Ditis e regno extraham

quidquid relictum est: ueniet inuisum Scelus

suumque lambens sanguinem Impietas ferox

Errorque et in se semper armatus Furor –

hoc hoc^ ministro~ noster utatur dolor.

^notice the anaphora (repetition) reflecting Juno's emotional state

~ablative object of utor

*like medius ("middle of"), imus can have a partitive meaning ("lowest part of" instead of just "lowest") as I suspect is true here.

I shall draw her forth and will drag out of the lowest (part of) the kingdom of Dis whatever is left over. There will come hated Crime, and ferocious Impiety licking her own blood and Error and Madness (who is) always armed against himself. This, this servant let our Grief employ. (I.e. Let our grief employ this as its servant.)

100

Incipite, famulae Ditis, ardentem citae

concutite pinum et agmen horrendum anguibus* *ablative of cause, similar to means

Megaera ducat atque luctifica manu

uastam rogo* flagrante corripiat trabem. *ablative of separation

hoc agite, poenas petite uiolatae Stygis*; *objective genitive

Begin, maidservants of Dis, roused (or as adverb "excitedly/madly") shake the burning pine and let Megaera lead your squad horrible with snakes and let her snatch with her grief-causing hand a vast log from a flaming pyre! Do this, seek out the penalties (i.e. revenge) for the violated/desecrated Styx.

By the way, I prefer vitiatae (E) over violatae (A) in line 104 because lectio difficilior potior est (The more difficult reading is the better one). This is a rule of textual criticism that says that given that there are two possible readings (and there are not other strong grounds for choosing between them), if one of the readings is quite easy to understand while the other is more difficult, the more difficult reading is more likely to be correct since it is less likely that someone would complicate the text than that they would accidentally or even purposefully banalize it (that is, explain away the difficulty by replacing it with a very easy to understand alternative). Personally I like the metaphorical meaning of vitiatae. Violatae is much more common and can mean physically violated in many different ways. Vitiatae implies corruption or befoulment, and one of the common senses of vitiare is "to deflower" or "to rape". Juno's feminine anger against Hercules' super-machoism may be displaying itself here. You should know that, besides being a river, Styx was also a very powerful goddess whom Zeus entrusted to watch over the oaths of the gods.

Friday, September 11, 2009

Senecan Anapaests and Steps for Scansion

STEPS FOR SCANSION

1. Elision

a. Check for elisions.*

b. Double check (remember final vowel + m elides, and h does not count).

*Caveat: Interjections will never elide. This makes sense since you would not want to blur or drop out such an emphatic word. Thus in "O iniuste" and "Vae amicos" there is no elision.

2. Mark known metrical values such as the final iamb in iambic trimeter.

3. Long by position

a. Mark all syllables that are long by position, i.e. followed by two consonants (or double consonants x or z) that are pronounced separately. Qu (and sometimes gu and su) counts as one consonant. Sometimes sc and st are pronounced together and count as one (at the beginning of words, not elsewhere).

b. Double check and make sure that you did not mark a syllable long if it may be short or long because it is followed by a mute + a liquid (r/l): pl, cr, dr, tr, fl, ...

4. Long or short by nature

a. Mark all syllables that you know are long or short because they contain diphthongs (au, oe, ae always; eu, ei, ui sometimes), because you know the ending (e.g. long o dative and ablative singular, long e in doces), or because you know the stem vowels (e.g. the preposition a is a long a, and ab has a short a; the perfect stem of video has a long i, and the present stem has a short i.).

b. Double check that you did not mark them incorrectly.

5. Finishing up

a. Now you should have most of the syllables scanned without guessing. Usually you can scan the rest of the line simply by knowing the metrical pattern (e.g. iambic trimeter) and filling in the appropriate values to fit the meter.

-Look for complete feet and metra to help orient you in the line; mark the boundaries between metra if you can tell.

-Where there is one unmarked syllable, see if it must be long or must be short according to the meter.

-Where there are two or more unmarked syllables in a row, look at the context to see which feet they might belong to. Then you may be able to tell whether you have two shorts in place of a long or anceps.

b. If all else fails, when doing homework you may look up words in a dictionary that has long marks to see the lengths (e.g. manus"hand" has a short a, manes "ghosts" has a long a). At this time you should also double check any from #4 that you were not 100% sure about.

6. After all syllables are scanned, put in any foot or metra marks that you had not made yet. Then mark your major caesura by looking for a word break that corresponds with a sense break in an appropriate metrical position (e.g. in the second metron after the first half of the first foot or after the first half of the second foot of an iambic trimeter line).

ANAPAESTS

An anapaest is a foot of three syllables, short short long (uu-).

In anapaestic verse, anapaests may be substituted with a spondee (--) or a dactyl (-uu).

Typically anapaestic stanzas are dimeter (two metra of two feet each) or trimeter (3 metra of two feet each). We will be scanning dimeter, though some short lines are just one metron (two feet). The caesura usually goes in the middle of the dimeter, so it is technically a diaresis, pause at foot break.

Examples

sidera prono languida mundo

- u u - - || - u u - -

nox victa vagos contrahit ignes

- - u u - || - u u - -

1. Elision

a. Check for elisions.*

b. Double check (remember final vowel + m elides, and h does not count).

*Caveat: Interjections will never elide. This makes sense since you would not want to blur or drop out such an emphatic word. Thus in "O iniuste" and "Vae amicos" there is no elision.

2. Mark known metrical values such as the final iamb in iambic trimeter.

3. Long by position

a. Mark all syllables that are long by position, i.e. followed by two consonants (or double consonants x or z) that are pronounced separately. Qu (and sometimes gu and su) counts as one consonant. Sometimes sc and st are pronounced together and count as one (at the beginning of words, not elsewhere).

b. Double check and make sure that you did not mark a syllable long if it may be short or long because it is followed by a mute + a liquid (r/l): pl, cr, dr, tr, fl, ...

4. Long or short by nature

a. Mark all syllables that you know are long or short because they contain diphthongs (au, oe, ae always; eu, ei, ui sometimes), because you know the ending (e.g. long o dative and ablative singular, long e in doces), or because you know the stem vowels (e.g. the preposition a is a long a, and ab has a short a; the perfect stem of video has a long i, and the present stem has a short i.).

b. Double check that you did not mark them incorrectly.

5. Finishing up

a. Now you should have most of the syllables scanned without guessing. Usually you can scan the rest of the line simply by knowing the metrical pattern (e.g. iambic trimeter) and filling in the appropriate values to fit the meter.

-Look for complete feet and metra to help orient you in the line; mark the boundaries between metra if you can tell.

-Where there is one unmarked syllable, see if it must be long or must be short according to the meter.

-Where there are two or more unmarked syllables in a row, look at the context to see which feet they might belong to. Then you may be able to tell whether you have two shorts in place of a long or anceps.

b. If all else fails, when doing homework you may look up words in a dictionary that has long marks to see the lengths (e.g. manus"hand" has a short a, manes "ghosts" has a long a). At this time you should also double check any from #4 that you were not 100% sure about.

6. After all syllables are scanned, put in any foot or metra marks that you had not made yet. Then mark your major caesura by looking for a word break that corresponds with a sense break in an appropriate metrical position (e.g. in the second metron after the first half of the first foot or after the first half of the second foot of an iambic trimeter line).

ANAPAESTS

An anapaest is a foot of three syllables, short short long (uu-).

In anapaestic verse, anapaests may be substituted with a spondee (--) or a dactyl (-uu).

Typically anapaestic stanzas are dimeter (two metra of two feet each) or trimeter (3 metra of two feet each). We will be scanning dimeter, though some short lines are just one metron (two feet). The caesura usually goes in the middle of the dimeter, so it is technically a diaresis, pause at foot break.

Examples

sidera prono languida mundo

- u u - - || - u u - -

nox victa vagos contrahit ignes

- - u u - || - u u - -

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Good reading

I have been reading for my own research and came across some interesting comments by Alastair Blanshard (Hercules, a Heroic Life, London: Granta Books, 2005) p. 39-61 on Hercules' madness and Euripides' and Seneca's plays on the subject. Blanshard's larger theme in the book is the ambiguity of Hercules as a model from antiquity to the modern day. Someone might want to EZBorrow it for a report or use it as a source for papers. We don't have it in the library here. Blanshard discusses various incidents in the myths of Hercules and examines ancient, medieval, Renaissance, and modern treatments of the episodes in literature, in other arts, and even in politics and pop culture.

Other items of general interest on the literary importance of Heracles include:

Anderson, A. R. (1928) “Heracles and his successors. A study of a heroic ideal and the recurrence of a heroic type,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 39: 7-58.

Galinsky, G. K. (1972) The Heracles Theme: The Adaptations of the Hero in Literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.

Other items of general interest on the literary importance of Heracles include:

Anderson, A. R. (1928) “Heracles and his successors. A study of a heroic ideal and the recurrence of a heroic type,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 39: 7-58.

Galinsky, G. K. (1972) The Heracles Theme: The Adaptations of the Hero in Literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Senecan Iambic Trimeter

I'll not repeat what others have already said on line about distinguishing short and long vowels in Latin verse and about elision and prodelision. See here and here

Seneca's iambic trimeter closely follows Greek trimeter but it is more regular. It is called trimeter because of three metra. Each metron has two feet like this: x - u -. In this pattern - is long, u is short and x is anceps (either short or long)

Thus the whole line divided into metra is : x - u - | x - u - | x - u -. A long or more rarely an anceps syllable may be replaced with two shorts--this is called metrical "substitution".

Note that every other foot is an iamb or its equivalent in length, namely the tribrach u u u (3 shorts). The first foot in each metron may also be - - (spondee) or u u - (anapaest) or - u u (dactyl) or u u u u (proceleusmatic), which are all one half measure longer than the iamb (u -) and tribrach (u u u).

Here is some iambic trimeter scansion from Seneca's Medea:

| indicates the separation between metra. Notice that this comes before a single consonant (se|d a|lius) even if this puts the final consonant of a word with the following word, but divide after the first consonant or consonant group when multiple consonants come between syllables (mon|strum)

|| indicates a major caesura or pause in the line due to word break and sense

Di coniuga|les || tuque geni|alis tori,

- - u - | - || - u u u | - - u -

Lucina, cus|tos || quaeque domi|turam freta

- - u - | - || - u u u | - - u x {The last syllable here is long because last in line.

Tiphyn nouam |frenare || docu|isti ratem,

- - u - | - - u || u u | - - u -

letumque socer(o) et || regiae stirpi date. {The o in socero elides.

- - u u u | - || - u - | - - u x {The last syllable here is long because last in line.

Note that all these examples follow Porson's Law, perhaps the most well known law of classical metrics, for which see here. It applies to Greek tragic verse (and somewhat to Seneca as he followed Greek practice closely). Basically if the anceps syllable beginning the third metron is long, then it must belong to the same word as the next syllable, unless one of the syllables is a monosyllabic word.

Seneca's iambic trimeter closely follows Greek trimeter but it is more regular. It is called trimeter because of three metra. Each metron has two feet like this: x - u -. In this pattern - is long, u is short and x is anceps (either short or long)

Thus the whole line divided into metra is : x - u - | x - u - | x - u -. A long or more rarely an anceps syllable may be replaced with two shorts--this is called metrical "substitution".

Note that every other foot is an iamb or its equivalent in length, namely the tribrach u u u (3 shorts). The first foot in each metron may also be - - (spondee) or u u - (anapaest) or - u u (dactyl) or u u u u (proceleusmatic), which are all one half measure longer than the iamb (u -) and tribrach (u u u).

Here is some iambic trimeter scansion from Seneca's Medea:

| indicates the separation between metra. Notice that this comes before a single consonant (se|d a|lius) even if this puts the final consonant of a word with the following word, but divide after the first consonant or consonant group when multiple consonants come between syllables (mon|strum)

|| indicates a major caesura or pause in the line due to word break and sense

Di coniuga|les || tuque geni|alis tori,

- - u - | - || - u u u | - - u -

Lucina, cus|tos || quaeque domi|turam freta

- - u - | - || - u u u | - - u x {The last syllable here is long because last in line.

Tiphyn nouam |frenare || docu|isti ratem,

- - u - | - - u || u u | - - u -

letumque socer(o) et || regiae stirpi date. {The o in socero elides.

- - u u u | - || - u - | - - u x {The last syllable here is long because last in line.

Note that all these examples follow Porson's Law, perhaps the most well known law of classical metrics, for which see here. It applies to Greek tragic verse (and somewhat to Seneca as he followed Greek practice closely). Basically if the anceps syllable beginning the third metron is long, then it must belong to the same word as the next syllable, unless one of the syllables is a monosyllabic word.

Friday, September 4, 2009

Senecan Style, Nature, Models, and Performance

Style

Seneca the Younger was the son of Seneca the Elder (see here, a famous rhetorician, and the unlce of the poet Lucan.

Almost all so-called silver age Latin is very rhetorical but Seneca and Lucan are particularly full of rhetorical devices and witty aphorisms such as those which Seneca the Elder endorses in his rhetorical treatises addressed to Seneca and his two brothers Annaeus Mela (Lucan's Dad) and Gallio.

Common rhetorical devices (also sometimes called poetic devices because of their common use in poetry) are: metaphor, simile, hyperbole, alliteration, assonance, consonance, onomatopoeia, chiasmus, synchysis, personification, apostrophe, anaphora, hyperbaton, asyndeton, polysyndeton, litotes, pleonasm (repetition and variation), rhetorical question, synecdoche, metonymy, and zeugma.

For description and English examples, see here and here

Chiasmus and synchysis both refer to artful use of word order, for which you should also know the terms golden and silver lines.

Seneca, like his nephew Lucan, is particularly fond of mottoes (Latin "sententiae") or brief, pithy statements. Seneca's Greek and Latin models including Euripides all have such sententiae, but they are very common in Seneca.

Another stylistic feature is his allusiveness, Seneca was working in a great literary tradition of Greek and Latin poets (and other authors). Anything he wrote about had been written about much before, and his words often echo or allude to earlier treatments of the subject. Whenever this happens, the reader is free to bring the earlier passage into his reading of Seneca. Sometimes when we consider an author's source(s) it informs and transforms our own understanding of the passage at hand.

As I mentioned in one of the introductory questions, we cannot deny that Seneca's life had some impact on his writing. Look out for references to philosophical beliefs not only of the Stoics but also of other schools, issues of creation and destruction, life and death, right and wrong, excessive emotion and self-control, etc. Also we do not know when exactly he wrote this play or the others, but he was certainly writing as a high-class aristocrat in an imperial autocracy. He may have started writing tragedies in exile from Caligula or Claudius. Can you see any references that might suggest contemporary relevance or interests?

Performance?

We just don't know for sure if Seneca ever staged these plays, or even if he read them before an audience of whatever size (though this seems very likely). However, Senecan plays have been staged successfully in modern times, and we know that plays could be staged by senators in Seneca's lifetime. (Tacitus Annales 11.13 At Claudius matrimonii sui ignarus et munia censoria usurpans, theatralem populi lasciviam severis edictis increpuit, quod in Publium Pomponium consularem (is carmina scaenae dabat) inque feminas inlustris probra iecerat.) Keep this question in mind and consider issues of staging: who is on stage and when, what props and gestures might accompany the words on the page, and finally are there things that are hard to understand without seeing it staged?

Seneca the Younger was the son of Seneca the Elder (see here, a famous rhetorician, and the unlce of the poet Lucan.

Almost all so-called silver age Latin is very rhetorical but Seneca and Lucan are particularly full of rhetorical devices and witty aphorisms such as those which Seneca the Elder endorses in his rhetorical treatises addressed to Seneca and his two brothers Annaeus Mela (Lucan's Dad) and Gallio.

Common rhetorical devices (also sometimes called poetic devices because of their common use in poetry) are: metaphor, simile, hyperbole, alliteration, assonance, consonance, onomatopoeia, chiasmus, synchysis, personification, apostrophe, anaphora, hyperbaton, asyndeton, polysyndeton, litotes, pleonasm (repetition and variation), rhetorical question, synecdoche, metonymy, and zeugma.

For description and English examples, see here and here

Chiasmus and synchysis both refer to artful use of word order, for which you should also know the terms golden and silver lines.

Seneca, like his nephew Lucan, is particularly fond of mottoes (Latin "sententiae") or brief, pithy statements. Seneca's Greek and Latin models including Euripides all have such sententiae, but they are very common in Seneca.

Another stylistic feature is his allusiveness, Seneca was working in a great literary tradition of Greek and Latin poets (and other authors). Anything he wrote about had been written about much before, and his words often echo or allude to earlier treatments of the subject. Whenever this happens, the reader is free to bring the earlier passage into his reading of Seneca. Sometimes when we consider an author's source(s) it informs and transforms our own understanding of the passage at hand.

As I mentioned in one of the introductory questions, we cannot deny that Seneca's life had some impact on his writing. Look out for references to philosophical beliefs not only of the Stoics but also of other schools, issues of creation and destruction, life and death, right and wrong, excessive emotion and self-control, etc. Also we do not know when exactly he wrote this play or the others, but he was certainly writing as a high-class aristocrat in an imperial autocracy. He may have started writing tragedies in exile from Caligula or Claudius. Can you see any references that might suggest contemporary relevance or interests?

Performance?

We just don't know for sure if Seneca ever staged these plays, or even if he read them before an audience of whatever size (though this seems very likely). However, Senecan plays have been staged successfully in modern times, and we know that plays could be staged by senators in Seneca's lifetime. (Tacitus Annales 11.13 At Claudius matrimonii sui ignarus et munia censoria usurpans, theatralem populi lasciviam severis edictis increpuit, quod in Publium Pomponium consularem (is carmina scaenae dabat) inque feminas inlustris probra iecerat.) Keep this question in mind and consider issues of staging: who is on stage and when, what props and gestures might accompany the words on the page, and finally are there things that are hard to understand without seeing it staged?

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

HF 12-29

Commentary for Hercules Furens 12-29

ferro- "with iron", metonymy, use of associated word instead of the exact noun. Probably here it refers to Orion's arrows, since he was a hunter. It is hard to see why Seneca includes Orion since he is neither a paelex of Jove nor the son of such a paelex. One story says he was born from Jove's semen (along with that of other gods) buried in the earth. If we remember that Gaea/Terra, the earth, was personified, this could mean that Juno presents this as a sort of affair. As Fitch points out, Orion was often associated with the previously mentioned Pleiades whom he supposedly chased. This along with the fact that he was a notorious attacker of the gods probably encouraged Seneca to include him.

minax- As often, this nominative adjective with an action verb may be translated as an adverb in English.

Perseus- The son of Zeus and Danae who was impregnated by Zeus' "golden shower". Thus the allusive epithet "golden".

Tyndaridae- The patronymic means "sons of Tyndareus", i.e. Castor and Pollux, who are also called the Twins (constellation Gemini) and the Dioscuri. The last name alludes to their birth from Zeus (Greek genitive Dios) and Leda. Zeus turned Leda (and himself) into a swan to fool Hera/Juno.

quibusque natis- At the birth of Apollo and Diana/Artemis, the children of Zeus and Leto, the island of Delos was supposed to have stopped floating randomly about, so stetit = "stood still". For this bit of myth, Callimachus may be the source (see here).

nec ipse...Cnosiacae gerit- Seneca alludes to Dionysus' deification, his mother Semele's deification, and the catasterism of Ariadne (the daughter of Minos from Knossos--thus by metonymy Cnosiaca), whom Dionysus wed. The point is not only did Zeus' lover and love child make it into heaven but even Dionysus' mortal paelex, Ariadne. The most influential telling of Ariadne's tale is Catullus', but Ovid's version (itself influenced by Catullus) may also be behind Seneca's allusion. The "puella" is snide. It connotes both youth and her status as the "mistress" or "girl" (a meaning often seen in Roman elegy or love poetry) of Dionysus.

tantum- meaning "only" here

ne qua- "lest any". After si, nisi, num and ne, all the ali's fall away. Thus qua equals aliqua, and it modifies pars

mundus- Munditia is neatness of appearance. Mundus as an adjective means neat, clean, elegant. Here as often mundus is used as a noun meaning "world" or "universe". The Greek word for universe is kosmos, which literally means "order" or "arrangement" and often referred to elegant physical appearance. Thus the Latin word mundus is what we call a calque. A calque is a word that is essentially a translation of a word from another language. That is, mundus did not mean "universe" until some Latin author (much earlier than Seneca) used it to translate kosmos.

sero- "late", i.e. "too late"

una...- She emphasizes that "one land", namely Thebes, has often provided offense. The allusion is to Alcmene, Semele, and Antiope, who were lovers of Zeus. The impiis may indicate further allusion to the impious daughters of Cadmus who killed Pentheus (In Euripides Bacchae).

novercam- "stepmother". In Latin, as English, stepmothers are proverbially wicked. There might be a tinge of this connotation here, though Juno would think her "evilness" justified. By the way, look out for rhetorical points that both fit and do not fit the character speaking. In the desire to make a witty rhetorical jab, Seneca (and to some extent Euripides before him) sometimes has a character say something that is out of character in order to make a point.

licet- As often even in prose, the conjunction licet (meaning "although") is postpositive, it always takes a subjunctive verb--here escendat, teneat, and occupet.

Alcmene- Greek 1st declension feminine singular, "Alcmene" the mother of Hercules. Alcmena is the common Latin nominative, but the Greek form with a long final e is needed here to fit the meter.

teneat...locum- Notice how these verbal repetitions (echoing locum in line 4 and tenent in 5) serve to round off this digression as Juno returns to the current situation--her hatred for Hercules, the latest (and according to some accounts, last) illegitimate son of Zeus.

astra...promissa- This suggests that Zeus has already promissed Hercules (natus, i.e. son of Alcmene) immortality or at least catasterism.

in cuius...- cuius refers back to Hercules (natus). The allusion here is to the myth that Zeus made the night last longer so that he could continue enjoying Alcmene before her husband returned.

ortus- acc. pl. m. literally "risings", a poetic way to refer to his conception

iubar- acc. s. n. "corona" or "brightness", the word specifically refers to the orb of diffuse light that emanates from a glowing body.

Oceano- ablative (without prep.) or locative of place where

vivaces...animus- Uncommon word order (chiasmus ABBA, synchysis ABAB) is common in poetry both for convenience (to fit meter) and for artful effect. Vivaces goes with iras and violentus with animus as you can tell by the endings. This example has Adj. A, Adj. B, Noun A, Noun B--an order which is usually called synchysis or interlocking word order by classicists, though sometimes chiasmus is used more generally for all such arrangements. Note also the alliteration of VIvaces & VIolentus. This may be understood as a sort of perverse figura etymologica. That is, through etymological word play the poet suggests a real relationship between two words of the same etymological root. Here VIolence makes Juno's anger VIvacious or full of life. The ancient authors use figura etymologica even in instances where the two words are only apparently and not really related.

tardusque...- Adj. A, Adj. B, Noun A, Noun B--synchysis again

aeterna bella pace sublata- Because of the inflexions which tell which words go together, Latin and Greek may be much more flexible in their word order even in prose, but especially in poetry. Here again we have artful word order (chiasmus of the noun-adjective ordering): Adj. 1, Noun 1, Noun 2, Adj. 2. I should point out that the word order allows the poet to tellingly juxtapose the antonyms bella and pace. Greek and Latin authors love to use word order like this to emphasize the opposition or association of two words or ideas. See 487 "unus una" for association by juxtaposition and 557 "uno tot" & 873 "segnis, properamus" for opposition by juxtaposition.

pace sublata- ablative absolute

ferro- "with iron", metonymy, use of associated word instead of the exact noun. Probably here it refers to Orion's arrows, since he was a hunter. It is hard to see why Seneca includes Orion since he is neither a paelex of Jove nor the son of such a paelex. One story says he was born from Jove's semen (along with that of other gods) buried in the earth. If we remember that Gaea/Terra, the earth, was personified, this could mean that Juno presents this as a sort of affair. As Fitch points out, Orion was often associated with the previously mentioned Pleiades whom he supposedly chased. This along with the fact that he was a notorious attacker of the gods probably encouraged Seneca to include him.

minax- As often, this nominative adjective with an action verb may be translated as an adverb in English.

Perseus- The son of Zeus and Danae who was impregnated by Zeus' "golden shower". Thus the allusive epithet "golden".

Tyndaridae- The patronymic means "sons of Tyndareus", i.e. Castor and Pollux, who are also called the Twins (constellation Gemini) and the Dioscuri. The last name alludes to their birth from Zeus (Greek genitive Dios) and Leda. Zeus turned Leda (and himself) into a swan to fool Hera/Juno.

quibusque natis- At the birth of Apollo and Diana/Artemis, the children of Zeus and Leto, the island of Delos was supposed to have stopped floating randomly about, so stetit = "stood still". For this bit of myth, Callimachus may be the source (see here).

nec ipse...Cnosiacae gerit- Seneca alludes to Dionysus' deification, his mother Semele's deification, and the catasterism of Ariadne (the daughter of Minos from Knossos--thus by metonymy Cnosiaca), whom Dionysus wed. The point is not only did Zeus' lover and love child make it into heaven but even Dionysus' mortal paelex, Ariadne. The most influential telling of Ariadne's tale is Catullus', but Ovid's version (itself influenced by Catullus) may also be behind Seneca's allusion. The "puella" is snide. It connotes both youth and her status as the "mistress" or "girl" (a meaning often seen in Roman elegy or love poetry) of Dionysus.

tantum- meaning "only" here

ne qua- "lest any". After si, nisi, num and ne, all the ali's fall away. Thus qua equals aliqua, and it modifies pars

mundus- Munditia is neatness of appearance. Mundus as an adjective means neat, clean, elegant. Here as often mundus is used as a noun meaning "world" or "universe". The Greek word for universe is kosmos, which literally means "order" or "arrangement" and often referred to elegant physical appearance. Thus the Latin word mundus is what we call a calque. A calque is a word that is essentially a translation of a word from another language. That is, mundus did not mean "universe" until some Latin author (much earlier than Seneca) used it to translate kosmos.

sero- "late", i.e. "too late"

una...- She emphasizes that "one land", namely Thebes, has often provided offense. The allusion is to Alcmene, Semele, and Antiope, who were lovers of Zeus. The impiis may indicate further allusion to the impious daughters of Cadmus who killed Pentheus (In Euripides Bacchae).

novercam- "stepmother". In Latin, as English, stepmothers are proverbially wicked. There might be a tinge of this connotation here, though Juno would think her "evilness" justified. By the way, look out for rhetorical points that both fit and do not fit the character speaking. In the desire to make a witty rhetorical jab, Seneca (and to some extent Euripides before him) sometimes has a character say something that is out of character in order to make a point.

licet- As often even in prose, the conjunction licet (meaning "although") is postpositive, it always takes a subjunctive verb--here escendat, teneat, and occupet.

Alcmene- Greek 1st declension feminine singular, "Alcmene" the mother of Hercules. Alcmena is the common Latin nominative, but the Greek form with a long final e is needed here to fit the meter.

teneat...locum- Notice how these verbal repetitions (echoing locum in line 4 and tenent in 5) serve to round off this digression as Juno returns to the current situation--her hatred for Hercules, the latest (and according to some accounts, last) illegitimate son of Zeus.

astra...promissa- This suggests that Zeus has already promissed Hercules (natus, i.e. son of Alcmene) immortality or at least catasterism.

in cuius...- cuius refers back to Hercules (natus). The allusion here is to the myth that Zeus made the night last longer so that he could continue enjoying Alcmene before her husband returned.

ortus- acc. pl. m. literally "risings", a poetic way to refer to his conception

iubar- acc. s. n. "corona" or "brightness", the word specifically refers to the orb of diffuse light that emanates from a glowing body.

Oceano- ablative (without prep.) or locative of place where

vivaces...animus- Uncommon word order (chiasmus ABBA, synchysis ABAB) is common in poetry both for convenience (to fit meter) and for artful effect. Vivaces goes with iras and violentus with animus as you can tell by the endings. This example has Adj. A, Adj. B, Noun A, Noun B--an order which is usually called synchysis or interlocking word order by classicists, though sometimes chiasmus is used more generally for all such arrangements. Note also the alliteration of VIvaces & VIolentus. This may be understood as a sort of perverse figura etymologica. That is, through etymological word play the poet suggests a real relationship between two words of the same etymological root. Here VIolence makes Juno's anger VIvacious or full of life. The ancient authors use figura etymologica even in instances where the two words are only apparently and not really related.

tardusque...- Adj. A, Adj. B, Noun A, Noun B--synchysis again

aeterna bella pace sublata- Because of the inflexions which tell which words go together, Latin and Greek may be much more flexible in their word order even in prose, but especially in poetry. Here again we have artful word order (chiasmus of the noun-adjective ordering): Adj. 1, Noun 1, Noun 2, Adj. 2. I should point out that the word order allows the poet to tellingly juxtapose the antonyms bella and pace. Greek and Latin authors love to use word order like this to emphasize the opposition or association of two words or ideas. See 487 "unus una" for association by juxtaposition and 557 "uno tot" & 873 "segnis, properamus" for opposition by juxtaposition.

pace sublata- ablative absolute

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

Getting Started, HF 1-11

This blog will be an on-going project in inter-class communication as I will be posting observations and commentary on the play that we are reading, Seneca's Hercules Furens. I expect you all to make regular contributions to the blog by posting responses to your reading of the play, to articles and other scholarship we read or discuss, and to any commentary that I provide. Here are some major questions to keep in mind:

1. How does Senecan tragedy compare with other kinds of tragedy that you are familiar with (ancient, medieval, or modern and from any culture)?

2. Why do you think Senecan Tragedy has had so many modern detractors? Why was it so popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance and so influential on early English tragedy? (Compare 3)

3. What do you think about what we might call the "Senecan Question"? That is, is he a talented playwright, and were his plays ever performed for a significant audience of his contemporaries?

4. Two related points: Despite the sometimes annoying distraction of being overly historical in literary criticism, we cannot deny that an author's life has some relationship to what he writes. So, first, do you see Seneca as a hypocrite who did not practice what he preached (i.e. Stoic philosophy)? Second, how does his lifetime dedication to philosophy relate to the content of his plays (especially the Hercules plays)?

5. How would you compare the experience of reading Seneca in Latin vs. English translation? What can you learn about Seneca and the play from reading the original Latin?

Commentary on Hercules Furens

A device used by many ancient dramatists is the divine prologue.

Soror Tonantis- Juno is describing herself. We might imagine her even pointing at herself as she speaks; often it helps us understand drama to imagine it being performed. Tonans = "The Thunderer", a common associative title for Jove. The poetic use of related words or titles in the place of the proper nouns is called "metonymy".

hoc enim- The enim retains its usual position as second word of its clause (called postpositive); enim, like nam, means "for" or "since" and usually introduces a clause which explains or elaborates on a preceding statement. This interjected comment is not so much for explanation as to display Juno's bitter emotional disRUPTion--thus it interRUPTs the flow of her introduction.

semper alienum- These two words go closely together and describe Jupiter as "perpetually another's"--i.e. not ever belonging to his rightful wife Juno. Alienus is the possessive adjective for alius (other, another), so in addition to "strange" or "alien" it often means "belonging to others".

Iovem- Juppiter, Iovis m. Jupiter (English has only 1 p, Latin 2), Jove. Of course, all oblique (non-nominative) cases come from the Iov- stem.

ac templa...aetheris- Notice the poetic word order, where summi and aetheris go together as their forms show. This is common in poetry because it can be both artful and useful for fitting the meter (which is here iambic trimeter). Probably templa means not "temples" but "regions", an archaic and etymological sense of the word. Aether is a transliterated Greek word and it refers specifically to the "upper air" as opposed to the aer or "lower air". Vidua can mean "single" or "unmarried", not always specifically "widowed", although, despite Fitch, I think it is most forceful (and "Senecan") to go with a strong translation as it most often refers to a woman who has lost her husband by death or divorce, and it clearly has an emotive tone here, "widowed", "bereft", or "jilted". It need not matter that she is not really widowed or divorced. The verb deserui seems to be what we often call a present perfect or true perfect which denotes a present state due to (recent) past action: "I have (just) left".

locumque...dedi- A bit of poetic repetition and variation, this line means much the same as the previous clause, but the change in wording makes it not simply redundant. The phrase "caelo pulsa" indicates that she has been violently forced out of heaven--clear exaggeration. She has supposedly given up her place to Jove's latest loves whom she dubs "call girls" (paelices)--again hyperbole, since Jove has not taken these mortal loves to live with him "in caelo". Seneca is just using hyperbole to set the stage for his coming allusions to various women who have been catasterized (made into a star or constellation).

paelices caelum tenent- The choice of verb suggests that these "ladies" have captured the heavens and now hold it in their power.

hinc...alta parte- In drama, demonstrative particles, like hinc, and adjectives (hic, ille, etc.) should generally be assumed to be accompanied by gesture. In this erudite list, the actor playing Juno (or the reciter if a solo performance) might motion to various spots in the sky as he said hinc "over here" or illinc "over there". One should note that, while hinc and illinc are actually adverbs of place from which, "from here" and "from there", Latin often uses source expressions ("from this side") where English prefers place where ("on/at this side"). The phrase "alta parte" which in Latin prose might be accompanied either by in (place where) or by ex (place from which) is best construed as place where in English.

Arctos- "The Bear". This constellation (Big Dipper or Ursa Major) is supposedly the catasterism of Jove's lover Callisto. Of course, as today, in the ancient world many astronomers and sailors used it to find the north pole--thus Seneca's glacialis polus which hints at the frigid temps of the North.

sublime...sidus- sidus, sideris n. usually means "constellation", as here, rather than "star" which is more likely stella or astrum. Notice the mild personification of sidus here as the subject of agit.

classes- Most commonly, as here, classes refers to "fleets" of ships, though the word can sometimes refer to other groups of people or things.

qua- qua (abl. s. f. from qui, quae, quod) as often understands a noun like parte or regione and thus means "where" or "in which place".

recenti vere- recenti (from recens, -ntis) is a "false friend"; it means "fresh" (i.e. "just starting") as usual, not "recent". Vere (from ver, veris n.) is ablative of time when which even in prose does not have a proposition.

Tyriae...nitet- Allusion to the myth of Zeus/Jupiter turning into a bull to steal Europa who was from Tyre. nitet ("glistens") obviously refers to the twinkle of the stars of the constellation Taurus ("The Bull") but also may allude to the glistening white color of the bull.

Atlantides- i.e. descendants of Atlas. The usual name for these daughters of Atlas and the sea nymph Pleione is the Pleiades, still a modern name for this star cluster which is in Taurus. Three of them, Maia, Electra, & Taygete bore Jupiter sons, respectively Mercury, Dardanus, & Lacedaemon.

1. How does Senecan tragedy compare with other kinds of tragedy that you are familiar with (ancient, medieval, or modern and from any culture)?

2. Why do you think Senecan Tragedy has had so many modern detractors? Why was it so popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance and so influential on early English tragedy? (Compare 3)

3. What do you think about what we might call the "Senecan Question"? That is, is he a talented playwright, and were his plays ever performed for a significant audience of his contemporaries?

4. Two related points: Despite the sometimes annoying distraction of being overly historical in literary criticism, we cannot deny that an author's life has some relationship to what he writes. So, first, do you see Seneca as a hypocrite who did not practice what he preached (i.e. Stoic philosophy)? Second, how does his lifetime dedication to philosophy relate to the content of his plays (especially the Hercules plays)?

5. How would you compare the experience of reading Seneca in Latin vs. English translation? What can you learn about Seneca and the play from reading the original Latin?

Commentary on Hercules Furens

A device used by many ancient dramatists is the divine prologue.

Soror Tonantis- Juno is describing herself. We might imagine her even pointing at herself as she speaks; often it helps us understand drama to imagine it being performed. Tonans = "The Thunderer", a common associative title for Jove. The poetic use of related words or titles in the place of the proper nouns is called "metonymy".

hoc enim- The enim retains its usual position as second word of its clause (called postpositive); enim, like nam, means "for" or "since" and usually introduces a clause which explains or elaborates on a preceding statement. This interjected comment is not so much for explanation as to display Juno's bitter emotional disRUPTion--thus it interRUPTs the flow of her introduction.

semper alienum- These two words go closely together and describe Jupiter as "perpetually another's"--i.e. not ever belonging to his rightful wife Juno. Alienus is the possessive adjective for alius (other, another), so in addition to "strange" or "alien" it often means "belonging to others".

Iovem- Juppiter, Iovis m. Jupiter (English has only 1 p, Latin 2), Jove. Of course, all oblique (non-nominative) cases come from the Iov- stem.

ac templa...aetheris- Notice the poetic word order, where summi and aetheris go together as their forms show. This is common in poetry because it can be both artful and useful for fitting the meter (which is here iambic trimeter). Probably templa means not "temples" but "regions", an archaic and etymological sense of the word. Aether is a transliterated Greek word and it refers specifically to the "upper air" as opposed to the aer or "lower air". Vidua can mean "single" or "unmarried", not always specifically "widowed", although, despite Fitch, I think it is most forceful (and "Senecan") to go with a strong translation as it most often refers to a woman who has lost her husband by death or divorce, and it clearly has an emotive tone here, "widowed", "bereft", or "jilted". It need not matter that she is not really widowed or divorced. The verb deserui seems to be what we often call a present perfect or true perfect which denotes a present state due to (recent) past action: "I have (just) left".

locumque...dedi- A bit of poetic repetition and variation, this line means much the same as the previous clause, but the change in wording makes it not simply redundant. The phrase "caelo pulsa" indicates that she has been violently forced out of heaven--clear exaggeration. She has supposedly given up her place to Jove's latest loves whom she dubs "call girls" (paelices)--again hyperbole, since Jove has not taken these mortal loves to live with him "in caelo". Seneca is just using hyperbole to set the stage for his coming allusions to various women who have been catasterized (made into a star or constellation).

paelices caelum tenent- The choice of verb suggests that these "ladies" have captured the heavens and now hold it in their power.

hinc...alta parte- In drama, demonstrative particles, like hinc, and adjectives (hic, ille, etc.) should generally be assumed to be accompanied by gesture. In this erudite list, the actor playing Juno (or the reciter if a solo performance) might motion to various spots in the sky as he said hinc "over here" or illinc "over there". One should note that, while hinc and illinc are actually adverbs of place from which, "from here" and "from there", Latin often uses source expressions ("from this side") where English prefers place where ("on/at this side"). The phrase "alta parte" which in Latin prose might be accompanied either by in (place where) or by ex (place from which) is best construed as place where in English.

Arctos- "The Bear". This constellation (Big Dipper or Ursa Major) is supposedly the catasterism of Jove's lover Callisto. Of course, as today, in the ancient world many astronomers and sailors used it to find the north pole--thus Seneca's glacialis polus which hints at the frigid temps of the North.

sublime...sidus- sidus, sideris n. usually means "constellation", as here, rather than "star" which is more likely stella or astrum. Notice the mild personification of sidus here as the subject of agit.

classes- Most commonly, as here, classes refers to "fleets" of ships, though the word can sometimes refer to other groups of people or things.

qua- qua (abl. s. f. from qui, quae, quod) as often understands a noun like parte or regione and thus means "where" or "in which place".

recenti vere- recenti (from recens, -ntis) is a "false friend"; it means "fresh" (i.e. "just starting") as usual, not "recent". Vere (from ver, veris n.) is ablative of time when which even in prose does not have a proposition.

Tyriae...nitet- Allusion to the myth of Zeus/Jupiter turning into a bull to steal Europa who was from Tyre. nitet ("glistens") obviously refers to the twinkle of the stars of the constellation Taurus ("The Bull") but also may allude to the glistening white color of the bull.

Atlantides- i.e. descendants of Atlas. The usual name for these daughters of Atlas and the sea nymph Pleione is the Pleiades, still a modern name for this star cluster which is in Taurus. Three of them, Maia, Electra, & Taygete bore Jupiter sons, respectively Mercury, Dardanus, & Lacedaemon.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)